Prime Minister Mark Carney’s visit to China is kind of a big deal — like, geopolitically big. It’s Ottawa signaling that it wants to un-awkward a very strained relationship with Beijing, all while Canada is also dealing with pressure and threats coming from the Trump administration. So yes, the timing is spicy.

On paper, the goals are super practical: talk trade, chase investment, and hopefully make China chill on those tariffs hitting Canadian canola, pork, and seafood. Cute, reasonable, fine. But let’s be clear — this trip is not about glossy photos or resurrecting some “strategic partnership” fantasy. The real test is whether Carney can walk away with actual economic wins without quietly compromising Canada’s long-term security or strategic independence. That means saying no to political pressure from Beijing, keeping economic security front and centre, and treating national security guardrails as mandatory, not optional.

Yes, Canada needs to diversify away from being overly dependent on the U.S. That part is real. But diversification does not mean blindly jumping into any economic relationship just because it exists. And nowhere is that more important than with the People’s Republic of China. China isn’t just “another market.” It’s a one-party state that openly uses economic ties as political leverage, and its geopolitical agenda is largely bad news for Canadian interests. Engagement with the Chinese Communist Party comes with strings — sometimes obvious, sometimes whispered — and silence on “core interests”. And that price is not cute.

Which brings us to Taiwan. Canada’s response to large-scale Chinese military drills around Taiwan in late December was delayed and unusually muted compared to other democracies. At a moment when Beijing was clearly testing international resolve, Ottawa hesitated. That hesitation doesn’t just land in Beijing — it’s also noticed in Taipei and among Canada’s democratic partners, raising questions about where Canada actually draws its red lines.

So can Canada pursue economic opportunity with China without sliding into deeper strategic dependence? That requires more nuance than “exports go up, everyone wins.” Economic security and resilience have to lead the conversation.

Where Canada is already heavily reliant on China, the goal should be risk reduction, not doubling down. Canola is the obvious case. Tariff relief matters, and Carney should push for it, but “restoring” the old status quo cannot be the endgame. Any deal needs a clear plan to diversify into other markets so Canada isn’t stuck in the same cycle next time tensions flare.

There are areas where engagement could make sense. Energy — both conventional and renewable — stands out as a sector where deeper ties could deliver real benefits without automatically lighting security alarms. But there are also hard no’s. Sensitive dual-use technologies, advanced AI, space and aerospace systems, critical infrastructure, and data-heavy ecosystems are not normal business sectors.

Finally, none of this works without serious national security vigilance. Trump-era pressure might be loud, but it doesn’t make PRC-related security risks disappear. Foreign interference, cyber intrusions, transnational repression, and research-security risks remain real. Periods of increased economic engagement are exactly when guardrails matter most.

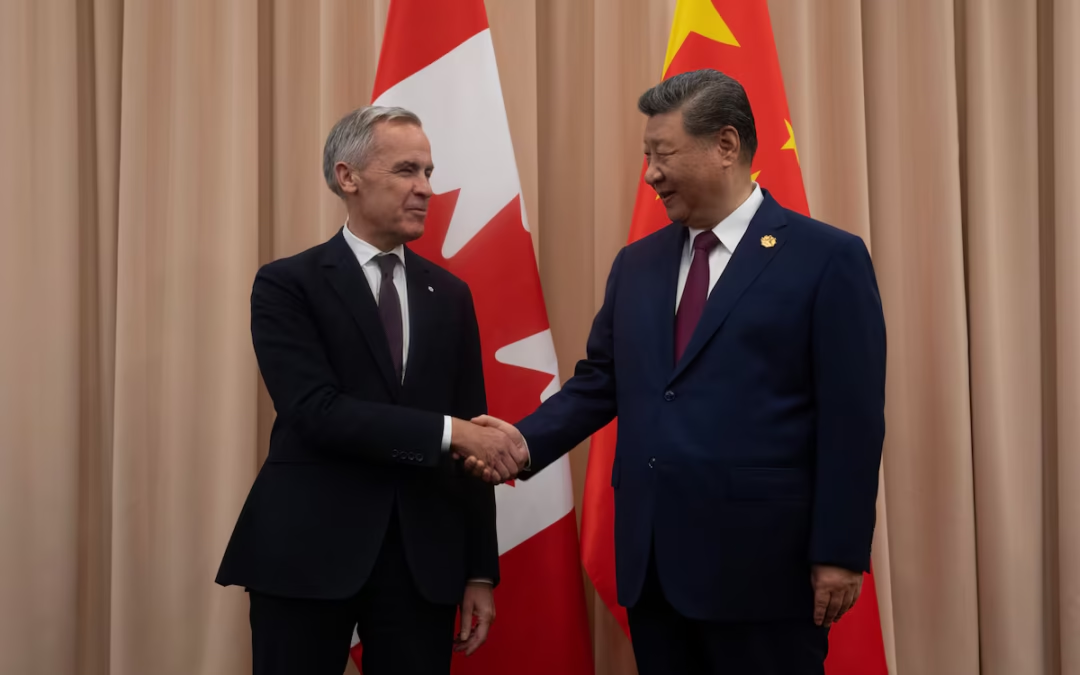

Mark Carney is right to test whether pragmatic diplomacy with China can deliver economic benefits. But dialogue is not trust, and trade is not alignment. The success of this trip won’t be measured by a handshake photo or a vague communiqué. It will be measured by whether Canada walks away with tangible gains — and stronger guardrails protecting its sovereignty, resilience, and security.

XOXO,

Valley Girl News

Canada, make it strategic — and not naïve